State in crisis: self-correction in Brazil

Staring at the neglected walls of the Palácio do Planalto in Brasília—paint chipping away from years of rain, wind and sun—one aspect of Brazilian democratic institutions continued to surprise me. In a system swarming with blatant inconsistencies, nothing stands out as much as the lack of self-correction in our democratic process.

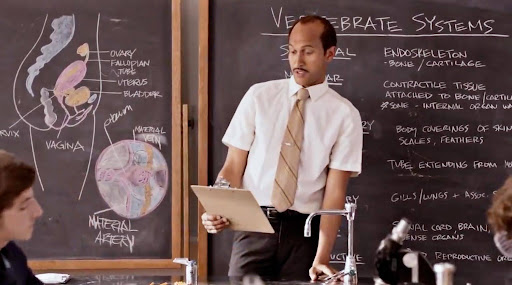

Since the fall of the dictatorship roughly thirty years ago, trust in Brazilian political institutions, be they parties, elections or administrations, has been in free fall. While Brazilian citizens are voting now more than ever before, the majority of people have lost the feeling that their individual votes really matter. That is perhaps why, when visiting the National Congress building, I had only to go up six floors to find myself at the office of Deputado Francisco Everardo Oliveira Silva, better known by his stage name as a clown: Tiririca.

But it wasn’t the flagrant disregard for constitutional rights when the public was denied access to the Senate hearings or the evasive answers of members of Congress on issues that ranged from energy to women’s rights that led me to believe that our democratic process has lost touch with the average Brazilian citizen. The problem lies in the political system’s inflexibility in the face of much-needed change.

With dishonest politicians that are reelected term after term, a thirty-party system that is overrun with corrupt men and women, and countless cases of senators whose net worth increases by millions while they are in office, the call for change could not come sooner. At its essence, the democratic process should be open to self-correction, since that is the only way to learn from past mistakes that make up the collective experience of the Brazilian people. But, as we’ve seen in these last few decades, either the Brazilian collective experience has failed to connect bad governing with bad candidates—we elected our almost-impeached ex-president Fernando Collor as senator just a few years ago—or the Brazilian democracy has failed us in correcting its past mistakes.

Of course there are exceptions. The “Lei da Ficha Limpa,” for example, is a clear preventive measure for ensuring that corrupt individuals are kept far away from the Senate floor. Some would look at the result of the demonstrations last year as cause for hope. While the lower transportation tariffs, the liquidation of the PEC 37, and the promise to redirect 75% of oil profits to education and 25% to healthcare were a “success,” these changes were only precipitated because 1.4 million people took to the streets. But such external factors should only aid the democratic process in its self-correction, not start them. Public demonstrations should be one of the last weapons in the political arsenal of each citizen; the government should be listening to its constituents’ call for smaller government, tax reform and an end to corruption. The Brazilian people should not have to take to the streets every time they want a law passed. That is not how a representative democracy should function.

The issue, however, is that the legitimacy of Brazilian democracy depends not on its capacity to bring prosperity, but on its capacity to correct what is dysfunctional, inefficient, or corrupt about its policies. The inability of the democratic institution of Brazil to self-correct is therefore a main reason behind the failure of our democracy. For now, much like the fading marble buildings in Brasília, our government can maintain its democratic façade, but a State that fails to correct its dysfunctional policies is, and always will be, in crisis.

Sources: globo.com, estadao.com