History: let’s get it right for once

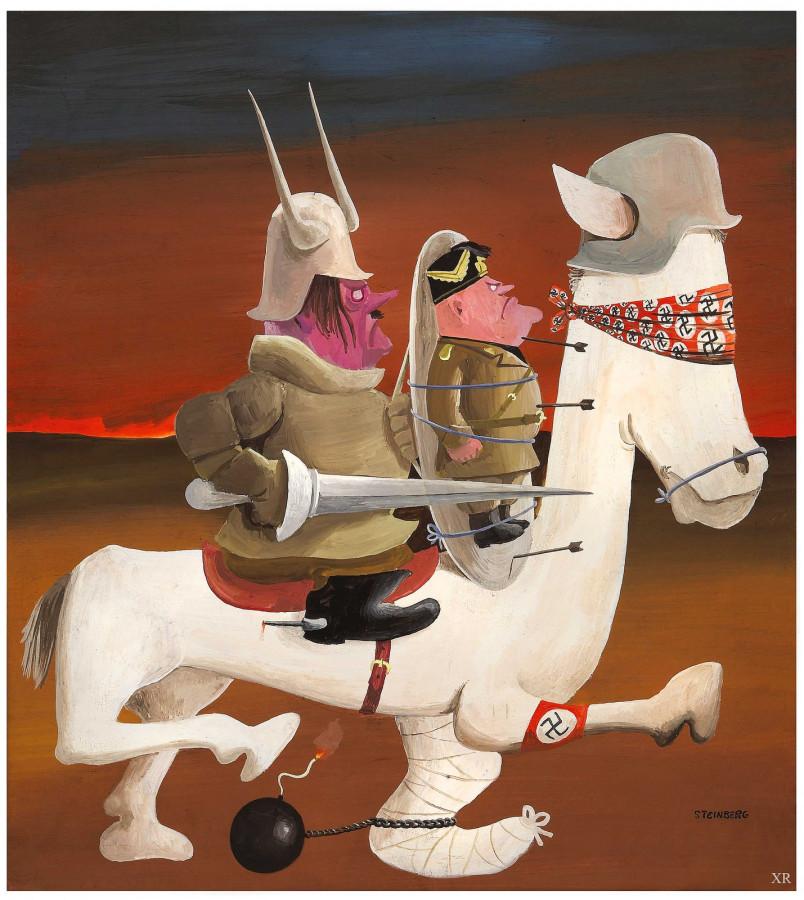

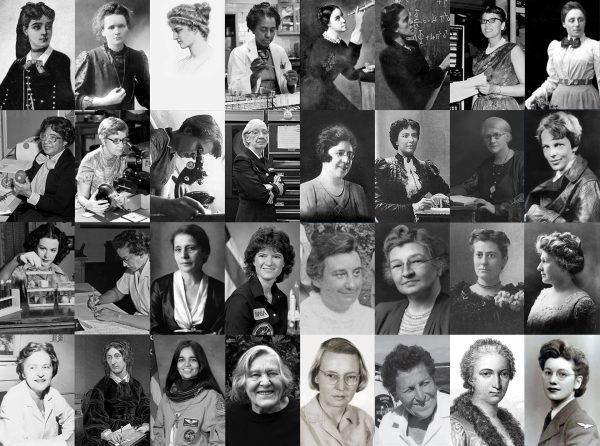

Recently, I stumbled on a Facebook post with the caption “Dear High Schoolers—question the history that is being taught to you.” Although I’m not sure about the accuracy of the post, the prompt is one to consider. Explaining that all women haven’t had the right to vote in the US since 1920 (only white women have), the post wants the reader to question the whitewashing of history and its teachings in the classroom. While mainstream history curricula—usually including the French Revolution and possibly major European dictators, such as Mussolini and Stalin—are extremely vital, learning history solely through those lenses excludes major voices in history.

Deciding what parts of history will be taught seems like an inordinate task, as illustrated by the IB History curriculum, with its multiple routes for learning the subject. As immense as it is, history cannot be taught in a few years. Even historians don’t specialize in all of history, but devote themselves to a specific era. To undertake the difficult task of deciding what parts of history to teach, we must ask, “What is the purpose of learning history?”

It really isn’t to “promote citizenship, [and] patriotism,” as defined by those in the state of Colorado in favor of a more right-wing-friendly curriculum. On the other hand, a lot of students have been subject to “popular history,” the curriculum presented in most US classrooms that stresses portraiture instead of analysis, thus evincing a distorted and superficial view of forces and events.

Even in some of the most scholarly contemporary studies on the making of the Constitution, for example, completed by scholars such as Jack Rakove and Bernard Bailyn focus on a clash of political ideology rather than the compromises that arose due to economic self-interest. As superb as their analyses are, they ignore practical realities and human frailty, thus portraying the United States’ founding fathers in a more patriotic light. It isn’t that the facts and analysis are wrong; it is just that those studies ignore a piece of history that could potentially shape or change the way that we perceive it.

The point is that the history we learn in the classroom is only one lens to analyze and understand it, as it is something that, according to Henry Glassie, author of The Practice and Purpose of History, “tangles the past with the present in a web of facts. Its practice is to treat things that exist here and now as though they concerned the past and to use them in new compositions designed to equip people for their trip into the future.”

History can then be studied through two possible processes. The first studies the present and its documents in order to speak about past cultures; the other studies the way people construct understandings of the past in order to speak about the culture in the present. Both methods facilitate our understanding of history in order to comprehend human behavior and systems, and they don’t use history as a tool to portray an image or twist facts. History is meant to be an instrument to understand relationships and events in our present day, which is why it is necessary to study it holistically.

By no means I am downplaying the importance of mainstream history; it just seems like the key to understanding history is to first know that there is always more. Unlike other subjects, history can be seen in a literal timeframe, the whole existence of the written record. History simply cannot be analyzed or even taught in a lifetime, and this is why prioritizing or defining the purpose of history to the student becomes essential. What we learn in history class is such a small portion of the timeline of humanity, a fragment in a bigger picture. History is vast; it hurts my head a little to think about how much more there is to know, and how—even if I think I’m learning so much—there is always more to consider.

Sources: articles.latimes.com; america.aljazeera.com; vice.com

On her third year on the Talon, Faria is serving as co-EIC with Michael Borger (God, help us all). As a senior, Faria discovered the key to success–and...