Designing a Dystopia

How City Planners Knowingly Moderate Our Behavior

In 2017, Blade Runner 2049 became one of the most popular motion pictures of the year. Movie critics and fans worldwide were dazzled by the new addition to Ridley Scott’s 1982 Blade Runner; a movie concerned with the nature of human beings as a means of advancing the plot. In his review, Brian Tallerico states that the film did a “great job at the futuristic aspects of their vision.”

However, what many of us don’t realize is that Blade Runner‘s atmosphere is not as elusive as we think it is. If we scrutinize our surroundings, we come to understand that we are, indeed, already living in a world of “futuristic” aspects. Despite that, there is one major disadvantage to this modernity: those in a position of authority can control our behavior. What has for many years been considered an intangible destiny for our civilization is now becoming part of its reality.

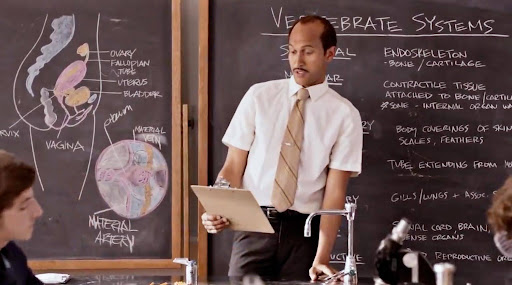

City designers have, for nearly a century, tried their best to ease the process in which governments control us. For instance, have you ever seen – while walking through the streets of New York City (or your nearest metropolis) – some benches that look inherently uncomfortable? They are the type of seat that force people to stand up again in a matter of minutes. Surprisingly (or rather expectedly), this is deliberate. That’s because, like in other large cities, the Big Apple has an ongoing issue with homelessness. As a result, the government of New York established an idea in urban design that alludes to Lyndon B. Johnson’s War on Poverty, albeit much more subtly. By manipulating our public environment, city planners have become the new, yet understated tyrants of today.

For the most part, urbanists take refuge amongst the most unconscious elements of our minds and use them as their sandbox. Specifically, this is what they call defensive design. Journalist Carlos Waters explains that “while designs can encourage positive behaviors, often they are designed to stop the opposite.” In other words, the same way that, say, barbed wire signals us that we can’t access a particular place, other very surreptitious geographical cues exist to perform the same function. Excluding the bad benches, other examples include menacing-looking spikes on concrete floors to expel skaters, armrests on large seats to avoid people from laying on them, and even sprinklers at the front of fancy restaurants to prevent homeless people from sleeping in their entryways.

Sadly, it seems that we might be addressing this issue erroneously. Although we have made tremendous progress regarding the question of adapting our cities and ourselves, we might have hindered the process in which social change can occur. “In terms of building social movements, a walkable city is important,” says Sarah Goodyear in her report on current urban environments. “Places where people literally brush up against each other on the sidewalk, where they have to be in public together […]. When people aren’t used to being together in the street, I think they’re less likely to go to the street and demand change.” Urbanists have established a society that is also susceptible to the blatant neglect of national affairs.

Now, it’s your turn to help. It’s your turn to recognize these overlooked patterns of authority. It’s your turn to express your freedom in ways that are intrinsic to the fabrics of community-building and metropolitan development. With that, when you see a set of sprinklers near a three Michelin star restaurant in New York City, you’ll know that the reason for why that’s there has been purposefully hidden from us.

Sources: Vox, CityLab, RogerEbert