The Impossible Movement

Cari’s blonde and I dyed my hair red, she has blue eyes and I have what my grandmother likes to call “honey, not poop, coloured eyes”. My twenty-year-old sister and I could not be more different, regardless of how many times we have been asked if we are twins. To further highlight our dissimilarities, our opposite personalities affirm our physical differences. She’s a messy type B that has a Mount-Everest-tall pile of clothes in the corner of her bedroom, while I’m a strict type A that has boring bedroom walls with a mere calendar as decoration. Yet regardless of these contrasts, our political and social ideas don’t diverge, or so I thought.

As quarantine would have it, Cari and I had the opportunity to learn that I am an extraordinarily gifted baker– a humble one too for that matter– while she is the synthesis of every contestant ever to participate in Netflix’s Nailed It! In between measuring cups and yoga sessions, our evening dog walks proved to be the most successful time to chat. Whether it be on our attempts at naming all the US states in under five minutes or talking about disturbing current events, our five o’clock walks allowed us to bond and grow closer. For the most part, we had fruitful conversations that enriched one another.

While I took some G+ courses over the summer, she began doing an online class called “International Women’s Health and Human Rights” taught by Stanford University. Some days we would share what we learned, and one specific day, she was telling me about female genital mutilation (FGM).

“More than 200 million girls and women alive today have been cut in 30 countries in Africa, the Middle East and Asia,” she said. She went into gruesome detail about the horrid that is FGM, and internally, I appreciated her being so explicit for the benefit of my knowledge. My stomach turned and knotted, making me feel sorrow in a matter of seconds.

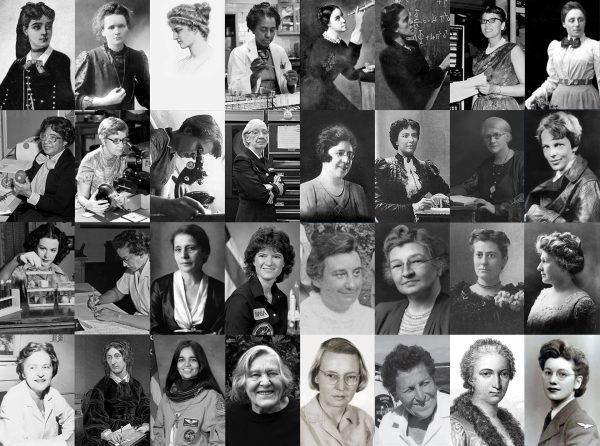

“That’s why we still need feminism!” I exclaimed. I spoke about the importance of feminism as a global movement that is still needed in corners all over the globe. I condemned anyone who believes that feminism is useless as ignorant people that are too blinded by their privilege. I was so crossed by the lack of vision to see that women’s equality is essential to the development of better living standards, growth of international peace, and economic as well as environmental sustainability of our entire civilization!

Then, an unexpected comment. “I don’t consider myself a feminist,” she said as she shrugged her shoulders.

Shocked, appalled, and curious.

“You’re not a feminist?! Estás loca?! Tipo, did you not hear what you just said?!” I roared.

She was totally unbothered. She knew me well enough to know this was going to be my reaction. We went back and forth for about thirty seconds of me just stating she was not a feminist and her replying with a calm and cool, “Yes, that’s what I said.”

I wanted to interrogate her about her beliefs because everything that I thought I knew about her was shaken to the core. But I didn’t, I stayed silent just as she was. We walked in silence for about a block, and then the conversation began. Soon enough, we were both steady and she started to explain. It’s not that she didn’t believe in women’s rights or gender equality, but rather that she believed that’s not what feminism stood for. I could see where she was coming from; feminism to her has become a ubiquitous label that is used in contexts ranging from FGM in African countries to the amendment of the Spanish constitution to write gender-inclusive language; clearly, one being more significant than the other.

She did not want to be associated with feminists that have excluded men from the movement, regardless of being half of the population and thus essential to progress. She did not want to be associated with feminists that shame other women for choosing to be feminine and “give into the patriarchy”. Most importantly– I suspect– she did not want to be associated with the feminists that had trashed the monument by which she and I walked past every day of our childhoods. Those feminists were not who she is. She wanted to be associated with feminists that gave Saudi women the right to drive. The ones that in Brazil pushed for a law on femicide to offer greater protection for women. And the ones that fought for 13 countries to establish legal frameworks for banning female genital mutilation.

But that’s the thing, how would people know which type of feminist she was?

“It’s an impossible movement,” she said. “There’s no consensus on what it means to be a feminist, and as a consequence, there’s no common goal.”

What first seemed like a complicated puzzle was now quite simple. She, like plenty of other people, believed in equality but did not feel comfortable using the word feminism because it partly embodies a series of ideals that do not align with hers.

As we crossed the street, I nodded in agreement. When she asked provoking questions like, can a woman be pro-life and still a feminist or can feminists respect a pro-life woman’s views? I found myself confused at what to reply. Not because I didn’t have an answer, but because my answer is not universal; and this, she pointed out, was the problem with the feminist movement.

Cari is currently a law student in Madrid, and despite not identifying as a feminist, she believes in gender equality. She hopes that as a lawyer she can be an active member of society that fights for equality, and to spend the rest of her life defending women so that when future students learn about FGM, they learn it as history, not current events, let alone a personal experience.

I, on the other hand, am not sure of what I want to do for the rest of my life but I know that for now, can call myself a feminist and participate in fighting for gender equality. I do not do so because I identify with the extremists of the movement nor because I’m gullible enough to believe that all feminists are good, but because I want to be part of the change. I want to look back and see that I belonged to a movement that, regardless of the failures, was defined by the successes. I want to evolve everyone’s idea of feminism and, alongside my sister, fight the same battle for gender equality; nothing more, nothing less.

Marina, also known as Nina, is thrilled to be a part of The Talon for her fourth and final year! On campus, Marina is always looking forward to lunch,...